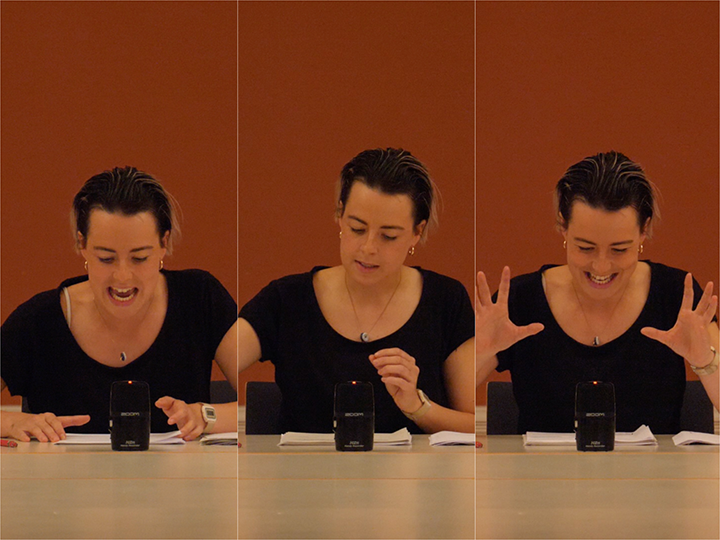

Figure 1. Eva Vogel (Floßhilde), Ida Aldrian (Wellgunde), Ania Vegry (Woglinde) during general rehearsal in Cologne 2021

(c) Heike Fischer

Dominik Frank (fimt – Research Institute for Music Theater Thurnau, University of Bayreuth)

The Research Institute for Music Theater Thurnau has joined forces with the orchestra Concerto Köln and the conductor Kent Nagano to find out, within the framework of the DFG-knowledge-transfer-project Wagner singing in the 21st century – historically informed, which historical singing techniques and style characteristics can be used for a historically informed performance of the Ring of the Nibelung within the framework of the project Wagner Readings1 and which aesthetic and content-related implications they contain. The project Wagner Readings, founded by Concerto Köln, the conductor Kent Nagano and now in cooperation with the Dresden Music Festival, has set itself the goal of extending historically informed performance practice, which is now well established in early music, to the repertoire of the Romantic period – and here in particular to The Ring of the Nibelung, which transcends all genre and format boundaries. The first goal is concert performances of all four Ring music dramas. Parts of this project are the reconstruction of historical instruments, scientific research on historical tempi and playing styles as well as an independent sub-project on pronunciation norms of the 19th century. Closely connected to the project is the aforementioned DFG-knowledge-transfer-project, which the Research Institute for Music Theater Thurnau (fimt) of the University of Bayreuth has acquired together with Concerto Köln. Within the framework of “Wagner singing in the 21st century – historically informed”, all questions of performing and singing are addressed. Based on the three aspects of speaking, singing and historical psychology, a program has been developed which offers the singers of the concert performances a variety of methods and possibilities to incorporate historical information into their performance of the parts. The most important aspect, according to Wagner, is the starting point of the musical design basing on the scenic-dramatic declamation and presentation. The model and paradigm for this kind of role design was the singer Wilhelmine Schröder-Devrient, who for Wagner was the model and ideal of the scenic-dramatic interpretation.2 A detailed description and scientific evaluation of this work will be made available in the final volume of the project. The digital essay presented here is devoted to the first sub-project, a reenactment of a solo reading performance of the Rheingold text, as Richard Wagner himself often performed and used as a starting point for his composition. The reenactment took place on Sept. 15, 2021, at Thurnau Castle, the seat of the research institute. This digital essay documents the reenactment both as an overall recording and in thematically focused excerpts that illuminate individual research findings. At the end of the essay, there is also a video showing the individual stages of implementation of the results with the singers of the three Rhinemaidens using an excerpt from the first picture of Rheingold.

Figure 1. Eva Vogel (Floßhilde), Ida Aldrian (Wellgunde), Ania Vegry (Woglinde) during general rehearsal in Cologne 2021

(c) Heike Fischer

The starting point for this reenactment were the research results of Martin Knust, who in his book Sprachvertonung und Gestik in den Werken Richard Wagners – Einflüsse zeitgenössischer Rezitations- und Deklamationspraxis3 (Speech Setting and Gesture in the Works of Richard Wagner – Influences of Contemporary Recitation and Declamation Practice) explained how strongly Wagner was influenced in his compositions by the theatrical art of his childhood and youth and the style of performance and recitation anchored in it. The theatrical-dramatic (and only secondarily musical) focus is also found in Wagner's high regard for the singer Wilhelmine Schröder-Devrient, whom he admired above all for her perfect acting-psychological grasp of her roles.4 Thus it was clear that the research of Wagner's singing ideal in the context of the project should start from such a reenactment (ostensibly without singing) of one of Wagner's solo reading performances.5 In the following, Martin Knust's research findings on this topic are briefly summarized before the reenactment is described in the next section.

Wagner himself was an enthusiastic and – if one believes contemporary reports – gifted reader. For Wagner, "reading aloud was a natural part of his everyday life. [...] His recital was essentially modeled on the acting declamation."6 Wagner's reading repertoire included his own dramatic poems as well as theoretical and autobiographical writings, complete dramas by other authors, novels, and philosophical texts. For drama lectures, among other things, an extensive Shakespeare recitation cycle, readings of plays by Schiller, Goethe, Calderón de la Barca, Lope de Vegas, and the "Greek classics from Aeschylus to Aristophanes"7 have been handed down. In addition, Wagner recited Homeric epics, texts of Indian antiquity, the Middle Ages, several times the novel Don Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes, as well as philosophical texts by Nietzsche, Schopenhauer, Plato and Aristotle.8 Wagner's reading style was characterized by a "dramatic-actor aplomb"9 that "certainly owed itself to the pathos of German stage declamation."10 Especially the distinction of the different roles by "art of characterization was generally praised."11 Eduard Devrient, for example, describes Wagner's performance style for Rheingold as follows: "There is to be admired in the various figures of the mermaids, dwarfs, giants, of Locke [=Loge], an [...] extraordinary power of characterization, and Wagner performs them with a virtuosity of presentation [...]."12

Knust argues the thesis, which has not yet emerged in research, that "it could have been [the] recitations [...] of his own poetry as a creative, artistically necessary process for him in the conception and composition of his dramas."13 According to Knust, Wagner "[i]n reciting [the Ring], he goes through his monumental work several times coram publico in order to test the dramatic effect on himself. [...] He will have shaped these lectures with all the performing and vocal means at his disposal. In the reading aloud, the temporal proportions of the work became apparent for the first time. In addition to the duration of sequences in the small, Wagner will also have gained clarity about those in the large."14 Wagner's creative process thus looked as follows: "The fixation of a mimic action – which [...] begins with the textbook – is followed at the beginning of the compositional creative process by the transfer into the imagined dramatic character. [...] From the sound, rhythm and tone of the spoken language, the singing voice is derived when the verses of the vocal text are set to music, and thus the 'word-tone melody' is obtained, which [...] is the starting point for the further composition".15

Starting from the ideal of the poet and performer in personal union16 and the ideal of "expropriation of self",17 the complete absorption of the performer in a character, Wagner thus sets to music the intuitively gained insights into the respective characters. He himself describes this process as follows: "Thus, by virtue of my intuition, I succeeded in putting myself completely into the nature of the mime, but only for the state into which he fell during the portrayal as a result of his successful expropriation of self, [the state] of ecstasy."18 Wagner refers to the writing down of this interpretation gained in "ecstasy" for re-interpretation by the singer-performers as "fixed improvisation[:] It is supposed to function like a 'transmigration of souls,' in which his idea spreads into performers and musicians in such a way that they inevitably carry it out as Wagner intended."19 For Wagner, "[t]he life-giving center of dramatic expression [...] is the performer's verse melody."20 Accordingly, he also composes from the word verse, "not from the read or written, but from the spoken word verse":21 "[T]he determining context of the melody lies [...] in the sensuous expression of the word phrase."22 And it was precisely for the exploration of this "sensuous expression[s]" that Wagner needed the repeated recitation of his texts. As a result, the score is strongly influenced by the speaking style of the reciting performer, according to Wagner's "own view [...] of the theatrical spoken performance of an epoch already past in 1872," the time of his theatrical influence in childhood and youth.23 The composition always follows the meaning, not the rhythm of the text, which corresponds to the declamation practice of the 19th century.24 Thus Wagner's reading performances pursue an important purpose: to secure the composition's connection back to the drama.

Figure 2. Amélie Haller: reading performance Rheingold, 15.09.2021

(c) Milena Galvan Odar

Figure 3. Amélie Haller: reading performance Rheingold, 15.09.2021

(c) Milena Galvan Odar

Since in our project the Wagnerian development process is to be reconstructed in as much detail as possible in the work with the singers, the reenactment of a Wagner solo reading performance of Rheingold (a staged reading of the complete Rheingold libretto including the stage directions by a single person in front of an audience) was the logical first step. The term reenactment is explicitly not understood as an intended 1:1 reconstruction of a historical event – such a reconstruction would be impossible per se. This impossibility arises on one hand from the disparate source situation, on the other hand from the special quality of theater as a transitory medium, which is based on the constant exchange between actors and audience (feedback loop) in the sense of bodily co-presence.25 Even if a historical one hundred percent reconstruction of the reading performance should hypothetically succeed, the performative event would inevitably be different due to the differently socialized audience of the 21st century. Rather, the reenactment is understood as comparable to the original legal sense of re-enacting (re-en-act) a law.26 The focus is thus on the question of which artistic, aesthetic and performative strategies of the original (and in what way) can also have an effect in our present and be made artistically usable. The title of the DFG-knowledge-transfer-project also refers to this focus, which explicitly anchors the starting point of the view from the 21st century on historical performance practice.

For the reenactment, a collaboration was arranged with the performer and theater scholar Amélie Haller, who had already worked with fimt in the context of the Artistic Research and Music Theater Initiative on the project Storms of applause and thus had prior experience with historical pronunciation.27 The work on the reenactment of the Rheingold reading performance was carried out in four digital pre-rehearsals as well as three full-day live rehearsals in the Ahnensaal of Thurnau Castle. Dominik Frank and Milena Galvan Odar were involved in all rehearsals, while Kai Hinrich Müller, Volker Krafft and Ulrich Hoffmann were also involved in the video pre-rehearsals. On the evening of the last day, there was a public workshop presentation followed by an audience discussion. Rehearsal work and presentation were completely documented by video recording, the audience discussion as an audio recording. The video excerpts used below are from the recordings of the dress rehearsal and the presentation on Sept. 15, 2021.

Wagner's reading performance usually took place BEFORE the composition. Martin Knust has demonstrated that Wagner also used these performances to test the dramaturgical conception, the timing and the effects of certain emphases28 – thus, to explicitly prepare the composition. Therefore, it was important for us to explicitly choose a performer who did not know the music of Rheingold in order to avoid distortion effects: Any person who had studied the work extensively (like the scholars involved in the project) would automatically think and speak along with the composition during the reading. Thus, the performance would not correspond to the parameter of the development sequence that we set as primary, which starts from the purely spoken word and transforms it into song only in the last step. This problem could be avoided by casting Amélie Haller, who works mainly in spoken theater and performance art.

In the rehearsal work with the singers following the reenactment for the concert performance of Rheingold on November 18 and 20, 2021, the starting point consequently was also the spoken performance. The rehearsal methodology followed Wagner's approach of a three-step procedure: In the first step, the texts are declaimed and recited without musical accompaniment like play texts; in the second, they are spoken rhythmically to the piano accompaniment. Only in the last step are the texts sung in the modern sense (but always starting from the speech tone). On the eve of the Rheingold premiere, this process was presented in the context of a discussion concert. The video shows a small excerpt from the first picture of Rheingold with Ania Vegry (Woglinde), Ida Aldrian (Wellgunde), Eva Vogel (Floßhilde) and Volker Krafft (piano). In the first step, the singers speak the text freely in the historical declamation style, i.e. similar to Amélie Haller in the reenactment of the solo reading performance. In the second step, the music is added, but the singers continue to speak, but now already in a fixed rhythm. In the third step - starting from the declamation - the transition into song is then shaped, but at some points, in the sense of Wagner's contrast dramaturgy, they deliberately continue to speak – a stylistic device of Wilhelmine Schröder-Devrient,43 whom Wagner described as ideal. For clarification, the singers in the video also perform the same passage once in 'normal' singing style. It becomes clear what dramatic effect these 'Schröder-Devrient moments' can have and how the listener's attitude of reception is directed by these 'disturbances' of the musical flow to the exact pursuit of the dramatic intention – completely in the sense of the music drama desired by Wagner.

For anyone interested and as material for further research, we provide here the complete recording of the Rheingold reading reenactment.

| Bauer 2008 | Oswald Georg Bauer, Josef Hoffmann: Der Bühnenbildner der ersten Bayreuther Festspiele, München 2008. |

| Borchmeyer 2006 | Dieter Borchmeyer (Ed.), Richard Wagner: Der Ring des Nibelungen. Live-Lesung im Residenztheater, 5 CDs, München 2006. |

| Cambrigde Dictionary 2022 | https://dictionary.cambridge.org/de/worterbuch/englisch/re-enactment (Access: 6. November 2024). |

| Danuser 2000 | Hermann Danuser, „Universalität oder Partikularität. Zur Frage antisemitischer Charakterzeichnung in Wagners Werk“; in: Richard Wagner und die Juden, ed. by Dieter Borchmeyer, Ami Maayani and Susanne Vill, Stuttgart/Weimar 2000, S.79–102. |

| Devrient 1909 | Hans Devrient (Ed.), Briefwechsel zwischen Eduard und Therese Devrient, Stuttgart 1909. |

| Fischer-Lichte 2012 | Erika Fischer-Lichte, Performativität. Eine Einführung, Bielefeld 2012. |

| Frank/Haller/Reupke 2020 | Dominik Frank, Amélie Haller and Daniel Reupke: „,Stürme von Beifall‘ – Bericht zum Reenactment Stürme von Beifall – KörperSprache im Nationalsozialismus im Rahmen der Ausstellung Hitler.Macht.Oper“, in: Hitler.Macht.Oper. Propaganda und Musiktheater in Nürnberg 1920–1950, ed. by Silvia Bier, Tobias Reichhard, Daniel Reupke and Anno Mungen, Würzburg 2020. |

| Frank 2025 | Dominik Frank (Ed.), Wagnertheater! - Historisch informiert?, Tagungsband zum gleichnamigen Symposium. München 2025 (=Thurnauer Schriften zum Musiktheater 49) |

| Knust 2007 | Martin Knust, Sprachvertonung und Gestik in den Werken Richard Wagners. Einflüsse zeitgenössischer Rezitations- und Deklamationspraxis, Berlin 2007. |

| Grimm 1980 | Jakob Grimm und Wilhelm Grimm (Ed.), Die schönsten Märchen, Erlangen 1980, S. 35–49. |

| Grotjahn 2020 | Rebecca Grotjahn, „,Eine wahrhaft deutsche theatralische Kunst‘ – Wilhelmine Schröder-Devrient und die Vorgeschichte der Wagner-Inszenierung“, in: Szenen-Macher. Wagner-Regie vom 19. Jahrhundert bis heute, ed. by Katharina Wagner, Holger von Berg and Marie Luise Maintz, Kassel 2020 (= Diskurs Bayreuth 3). |

| Monschau 2020 | Christina Monschau, Mimik in Wagners Musikdramen. Die Selbstentäußerung als Bedingung und Ziel?, Würzburg 2020. |

| Mungen 2021 | Anno Mungen, Die dramatische Sängerin Wilhelmine Schröder-Devrient. Stimme, Medialität, Kunstleistung, Würzburg 2021 (= Thurnauer Schriften zum Musiktheater 37). |

| Wagner 1907 | Richard Wagner, Gesammelte Schriften und Dichtungen, 10 Bände, Leipzig 1907. |

| Wagner 1958 | Richard Wagner, Das Rheingold: Complete recording (Conductor: Sir Georg Solti, Wiener Philharmoniker, 1958), Decca 2 CDs ADD 59, 1997. |

| Wagner 2010 | Richard Wagner, Das Rheingold, Piano reduction with rehearsal notes by Heinrich Porges. Schott 2010. |

| Wagner Lesarten 2022 | https://wagner-lesarten.de/beschreibung.html (Access: 6. November 2024). |

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Keywords: Wagner, historisch informierte Aufführungspraxis, Rheingold, Reenactment

Dominik Frank